Nat’s Chats

reflections on the last month at City to Sea HQ

Summer is here in the UK, and June, which is normally our busiest month of the year, was turned on its head. World Refill Day was another corona-casualty – postponed due to the pandemic. Half the team were furloughed, and we took a fair bit of flak for our supportive stance on recent events in our home city of Bristol.

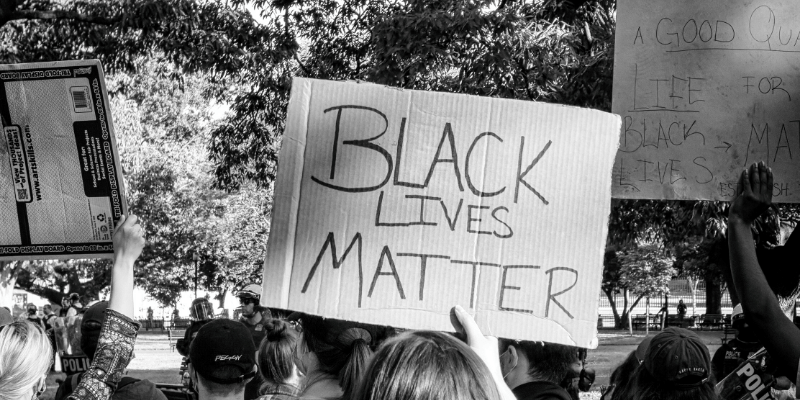

Speaking out

Aside from launching two successful new campaigns to stop the onslaught of plastic ‘covid-waste’, we’d spoken out about Black Lives Matter. Sharing our journey as a predominantly white, privileged, female-run organisation to becoming more diverse. We reflected on the lack of representation of black and brown people in the environmental movement – especially in Bristol. We celebrated the toppling of our city’s statue of a prominent slave trader. And as a result, 415 people unsubscribed from our mailing list.

Some told us to ‘stay focused on plastic pollution’ and some were just plain nasty. But we didn’t take it personally. Social issues like racism, are often seen as separate to environmental issues. I thought they were too, until about a year ago. I believed that “We’re busy working to save the oceans and the planet, you guys are busy working on social issues. And that’s cool.” But then I heard Sara Telahoun, a Bristol-based sustainability consultant, speaking about the links between environmentalism, conservation and colonialism. I started educating myself on intersectional environmentalism. Understanding how social and environmental issues overlap and seeing how the people who are most adversely affected by environmental problems are usually those that hold less privilege.

Intersectional Environmentalism

When it comes to plastic pollution, the intersection of social issues with environmental ones is strikingly clear once you look at how and where plastic is made, and where it ends up. So let’s take a quick look at that now. 99 percent of plastic is made from fossil fuels. Which means the fossil fuels (oil and gas) need to be extracted from the ground and then chemically processed, mostly in the US. Now, who are the people most likely to be living close to chemical plants and fracking sites and getting sick from poor air quality and contaminated water? Affluent white folk? Nope. It’s mostly BIPOC (black, indigenous and people of colour) communities. This is what’s called pollution inequity, or a pollution burden; a disparity between the pollution that people cause and the pollution to which they are exposed.

At the other end of plastic’s toxic lifecycle, once it’s considered waste, marginalised communities around the world are again bearing the toxic brunt. From living near landfill sites to having to work in extremely hazardous conditions sorting contaminated plastic waste by hand to find the higher value PET, to breathing in poisonous gases from incinerators. Our plastic waste harms humans as much as it harms marine life. So yes, plastic pollution is most definitely a social issue as well as an environmental one.

Learning and Healing

We totally get it that for lots of people, that connection hasn’t been made before. Even as a campaigning organisation we didn’t get it until relatively recently. But we’re here now. Trying to make sense of our broken world, trying to heal it while we heal ourselves of our own ignorance. And we’re really grateful that you’re sticking here with us.

Maybe this month, for the rest of #PlasticFreeJuly, you could try following the hashtag #intersectionalenvironmentalism and hear from some diverse voices around the world. For a deeper dive into the subject, have a read of ‘A Reality Check on Environmental Racism & Plastics’ (a brilliant article from the Surfrider Foundation). And – if you didn’t catch our screening of The Story of Plastic – now’s the time to watch it. It’s absolutely unmissable.